The road to an R01

...and whether K awards help you get there

If you want to understand the world of NIH grants, you could do worse than to use the lens of Darwinian evolution. Each mechanism has developed to occupy a niche where it can survive under dual selection pressures: first, it has to provide something appealing enough that capable researchers submit applications; and second, it has to be accepted as a signal of researcher quality by both universities and grant reviewers.

The apex predator in this metaphor is the R01, innocuously called the “Research Project Grant.” This grant provides funding for an ambitious set of aims over 3 to 5 years, with an average annual budget of between $300,000 and $500,000. It’s enough to hire people for your lab, and is a royal road to promotion in a lot of soft-money settings.

R01 grants are notoriously tough to get, and so there’s a whole subset of grant mechanisms designed to prepare you for a successful R01 application. Some of these are other research (i.e., “R”) grants designed for smaller projects (R03) or for exploratory data collection (R23). But the kind that interests me the most are the K awards, which are designed for career development.

K awards, though, tend to combine low salaries with substantial demands on your time. For instance, the K01 (for non-clinical researchers) requires 75% of your working time but pays just $90,000; the equivalent mechanism for researchers with clinical degrees (K08) offers a maximum of $105,000 for the same time commitment. The application also requires a structured career development plan that can include classroom time, professional shadowing, and other didactic activities. They also last for five years, meaning that they’re not a trivial commitment.

I couldn’t make sense of why people apply for K awards, so I asked about it on Twitter. The responses were great! My little network managed to spread it around to other academics so that it got attention from people I’m not directly connected to. The general advice was that K awards buy you time away from teaching and administrative responsibilities that you can use to launch your research program.

I wanted to see whether K awards actually help you get an R01. Thankfully, NIH has the ExPORTER — a public data source on all funded grants. What follows are my explorations of that data. All code is up on Github.

What grants do researchers get before their R01?

The data goes back to 1985, so I decided to focus on researchers who got their first R01 in 2000 or later. That would mean at least 15 years of observed time in which to accumulate other grants. Then, I simply traced back the types of awards that they got on their path to the R01. Note that I focused on types of awards, rather than actual grants — they could have received multiple awards within each of the categories I created.1

The maximum count of grant types received prior to an R01 was 5, but this was in a vanishingly small portion of the grantees — just 2 out of a total 47,266. The K awards are reasonably well represented in this cohort, about 20% of whom received an early career award. The small project R awards are a little more common: 22% of R01 recipients had received at least one.

What really surprised me, though, was that a majority of R01 recipients — 55% — hadn’t received any prior K or R awards. Since it’s possible to share the principal investigator role in an R01, were these folks just riding the coattails of more senior researchers into their awards? I looked into this and found that just 13% of researchers who got an R01 without prior K or R awards shared the principal investigator role in their first R01.

Are there time trends in the probability of getting your first R01?

The year 2000 was the approximate midpoint of a major change in the NIH called “The Doubling.” Between 1998 and 2003, the NIH’s budget doubled and the institute’s reach expanded considerably. Since that time, it’s taken steps to support early career researchers by creating mechanisms that you can only apply for if you haven’t had prior large awards and by prioritizing applications from these researchers. I wondered if you could see this change over time in the proportion of R01 awards going to grants where at least one of the principal investigators was a first-time R01 grantee.

If anything, there’s a declining trend in the share of R01 awards that go to grants with a first-time grantee as principal investigator — a drop of roughly 5 percentage points between 2000 and 2023. Still, the percentages are higher than I expected given the reputation of the R01.

(Funny enough, it took me a minute to figure out why there was such a huge drop for projects starting in 2009… It seems like the financial crisis of 2008 had made NIH much more conservative about funding new investigators.)

Do K awards improve your odds of an R01?

Next, I wanted to see if getting an early career K award actually improves your chances of landing an R01. This seems like a clear application of case-control methodology: I would simply collect information on a group of people who got an R01 and another group who didn’t, then compare the probability of having received an early career K award in those groups.

The challenge of this is that ExPORTER only includes successfully funded applications, making the identification of a control group without R01s harder. I settled on doing the analysis among the group of people who’d received dissertation R awards (R36s), pre-doc individual fellowships (F30s and F31s), and post-doc individual fellowships (F32s). This isn’t an ideal cohort: people who received these awards are pushing towards academic careers early on, and might not be representative of all the researchers who apply for R01s. Still, these awards are a clear indication of when their recipients were in training and were valuable for that reason. I only considered people who’d received one of these awards prior to 2015, which would give them enough time to launch their academic careers after their training completed.

ExPORTER had 33,467 recipients of R36s, F30s, F31s, and/or F32s. You can see the distribution of their award histories below:

Even among this select group that seems destined for academia, participation in grants indicative of an academic career is pretty low. The early career K awards, though, were extremely helpful: I calculated an odds ratio of 3.3, with a 95% confidence interval of 3.0 to 3.6. P-values were obviously way below 0.001.

This is more or less consistent with a 2019 study by Nikaj and Lund that examined R01 and its equivalents prior between 1990 and 2016. That study had reviewer scores from the K award sections, though, so the comparison group is different from the one that I had to use. They found a 24% increase in the likelihood of an R01 among recipients of an early career K award.

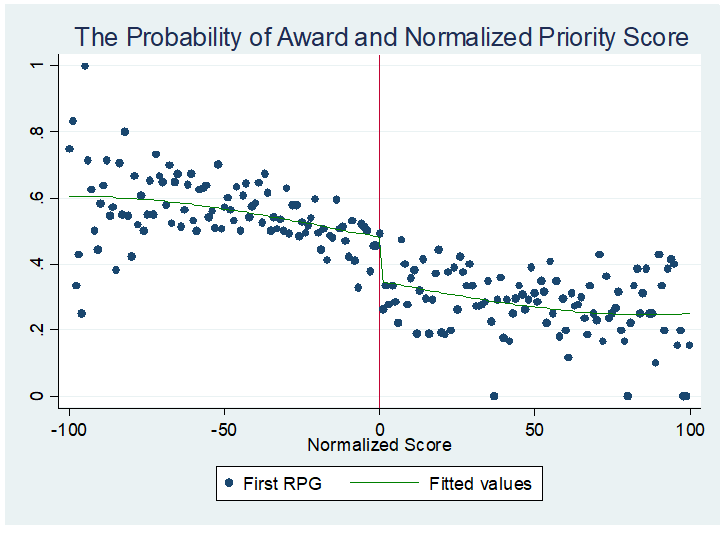

In the image below, those with a score below 0 received the K award, while those on the right side didn’t. The discontinuity at the 0 point seems unimpressive to me, honestly, and I think a better fitting model could’ve been created. My interpretation of this is that the probability of an R01 is predictable based on the priority score of a K award — likely a rough but legitimate signal of researcher quality — but that the actual receipt of a K award has relatively minimal counterfactual importance.

Wrapping up

The evidence on the relationship of early career K awards to the receipt of an R01 is difficult to assess, because K awards are likely to be correlated with a combination of both talent and the pursuit of a kind of well-trod path towards academic success. It’s not clear at all to me that we should interpret my findings or those of Nikaj and Lund in a counterfactual manner — that is, that an early career K award would improve the chances of an R01 for a given researcher. If it does help, it’s likely that it works through the mechanism that my Twitter interlocutors proposed: it clears enough time away from day-to-day academic responsibilities to establish a research program. This means that the K award would likely be a worthwhile investment of time and energy for folks in a traditional academic setting.

My posing these questions was not purely disinterested. I was strongly considering applying for a K award this summer and have become convinced that it doesn’t offer anything special to me. I have plenty of protected time — I don’t teach and my administrative responsibilities are minimal. Plus, whatever the impact of an early career K would be, it often takes years of preparation and failed applications to actually get one. After looking at the numbers, I’m reasonably confident that my time is better spent targeting R awards directly.

Here’s the schema I used. Early Career Development awards are K01, K07, K08, K09, K11, K14, K15, K16, K22, K23, K25, and K99/R00. Mid/Senior Career Development awards are K02, K04, K05, K06, K24, and K26. Small Research Project awards are R03 and R21. Research Education and Enhancement awards are R13, R15, R18, R24, R25, R34, and R35.